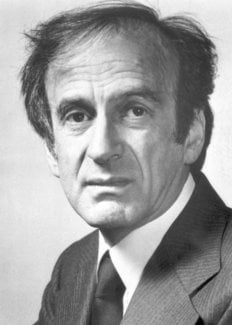

Biographical

Elie Wiesel was born in 1928 in the town of Sighet, now part of Romania. During World War II, he, with his family and other Jews from the area, were deported to the German concentration and extermination camps, where his parents and little sister perished. Wiesel and his two older sisters survived. Liberated from Buchenwald in 1945 by advancing Allied troops, he was taken to Paris where he studied at the Sorbonne and worked as a journalist.

In 1958, he published his first book, La Nuit, a memoir of his experiences in the concentration camps. He has since authored nearly thirty1 books some of which use these events as their basic material. In his many lectures, Wiesel has concerned himself with the situation of the Jews and other groups who have suffered persecution and death because of their religion, race or national origin. He has been outspoken on the plight of Soviet Jewry, on Ethiopian Jewry and on behalf of the State of Israel today.

Wiesel has made his home in New York City, and is now a United States citizen. He has been a visiting scholar at Yale University, a Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at the City College of New York, and since 1976 has been Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University where he teaches “Literature of Memory.” Chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council from 1980 – 1986, Wiesel serves on numerous boards of trustees and advisors.

Acceptance Speech

Elie Wiesel held his Acceptance Speech on 10 December 1986, in the Oslo City Hall, Norway.

(The speech differs somewhat from the written speech.)

It is with a profound sense of humility that I accept the honor you have chosen to bestow upon me. I know: your choice transcends me. This both frightens and pleases me.

It frightens me because I wonder: do I have the right to represent the multitudes who have perished? Do I have the right to accept this great honor on their behalf? … I do not. That would be presumptuous. No one may speak for the dead, no one may interpret their mutilated dreams and visions.

It pleases me because I may say that this honor belongs to all the survivors and their children, and through us, to the Jewish people with whose destiny I have always identified.

I remember: it happened yesterday or eternities ago. A young Jewish boy discovered the kingdom of night. I remember his bewilderment, I remember his anguish. It all happened so fast. The ghetto. The deportation. The sealed cattle car. The fiery altar upon which the history of our people and the future of mankind were meant to be sacrificed.

I remember: he asked his father: “Can this be true?” This is the twentieth century, not the Middle Ages. Who would allow such crimes to be committed? How could the world remain silent?

And now the boy is turning to me: “Tell me,” he asks. “What have you done with my future? What have you done with your life?”

And I tell him that I have tried. That I have tried to keep memory alive, that I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.

And then I explained to him how naive we were, that the world did know and remain silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must – at that moment – become the center of the universe.

Of course, since I am a Jew profoundly rooted in my peoples’ memory and tradition, my first response is to Jewish fears, Jewish needs, Jewish crises. For I belong to a traumatized generation, one that experienced the abandonment and solitude of our people. It would be unnatural for me not to make Jewish priorities my own: Israel, Soviet Jewry, Jews in Arab lands … But there are others as important to me. Apartheid is, in my view, as abhorrent as anti-Semitism. To me, Andrei Sakharov‘s isolation is as much of a disgrace as Josef Biegun’s imprisonment. As is the denial of Solidarity and its leader Lech Walesa‘s right to dissent. And Nelson Mandela‘s interminable imprisonment.

There is so much injustice and suffering crying out for our attention: victims of hunger, of racism, and political persecution, writers and poets, prisoners in so many lands governed by the Left and by the Right. Human rights are being violated on every continent. More people are oppressed than free. And then, too, there are the Palestinians to whose plight I am sensitive but whose methods I deplore. Violence and terrorism are not the answer. Something must be done about their suffering, and soon. I trust Israel, for I have faith in the Jewish people. Let Israel be given a chance, let hatred and danger be removed from her horizons, and there will be peace in and around the Holy Land.

Yes, I have faith. Faith in God and even in His creation. Without it no action would be possible. And action is the only remedy to indifference: the most insidious danger of all. Isn’t this the meaning of Alfred Nobel’s legacy? Wasn’t his fear of war a shield against war?

There is much to be done, there is much that can be done. One person – a Raoul Wallenberg, an Albert Schweitzer, one person of integrity, can make a difference, a difference of life and death. As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our lives will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.

This is what I say to the young Jewish boy wondering what I have done with his years. It is in his name that I speak to you and that I express to you my deepest gratitude. No one is as capable of gratitude as one who has emerged from the kingdom of night. We know that every moment is a moment of grace, every hour an offering; not to share them would mean to betray them. Our lives no longer belong to us alone; they belong to all those who need us desperately.

Thank you, Chairman Aarvik. Thank you, members of the Nobel Committee. Thank you, people of Norway, for declaring on this singular occasion that our survival has meaning for mankind.

Ընդունման խոսք

Էլի Վիզելը 1986 թվականի դեկտեմբերի 10-ին Նորվեգիայի Օսլոյի քաղաքապետարանում անցկացրեց իր Ընդունման ելույթը:

(Ելույթը որոշ չափով տարբերվում է գրավոր խոսքից):

Խոնարհության խոր զգացումով եմ ընդունում այն պատիվը, որը դուք ընտրել եք ինձ շնորհելու համար: Ես գիտեմ, որ քո ընտրությունը գերազանցում է ինձ: Սա ինձ և՛ վախեցնում է, և՛ ուրախացնում:

Դա ինձ վախեցնում է, քանի որ մտածում եմ՝ ես իրավունք ունե՞մ ներկայացնելու զոհված բազմությանը: Ես իրավունք ունե՞մ նրանց անունից ընդունելու այս մեծ պատիվը։ … Ես չեմ. Դա ամբարտավան կլիներ: Ոչ ոք չի կարող խոսել մահացածների փոխարեն, ոչ ոք չի կարող մեկնաբանել նրանց խեղված երազներն ու տեսիլքները:

Դա ինձ հաճելի է, քանի որ կարող եմ ասել, որ այս պատիվը պատկանում է բոլոր վերապրածներին և նրանց երեխաներին, և մեր միջոցով՝ հրեա ժողովրդին, որի ճակատագրի հետ ես միշտ նույնացել եմ:

Հիշում եմ՝ դա եղել է երեկ կամ հավերժություններ առաջ։ Երիտասարդ հրեա տղան հայտնաբերեց գիշերվա թագավորությունը: Հիշում եմ նրա տարակուսանքը, հիշում եմ նրա վիշտը։ Ամեն ինչ տեղի ունեցավ այնքան արագ: Գետտոն. Տեղահանությունը. Կնքված անասնագոմը. Կրակոտ զոհասեղանը, որի վրա պետք է զոհաբերվեր մեր ժողովրդի պատմությունը և մարդկության ապագան:

Հիշում եմ. նա հարցրեց հորը. «Կարո՞ղ է դա ճիշտ լինել»: Սա քսաներորդ դարն է, ոչ թե միջնադարը: Ո՞վ թույլ կտա նման հանցագործություններ կատարել։ Ինչպե՞ս կարող էր աշխարհը լռել:

Եվ հիմա տղան դիմում է ինձ. «Ասա ինձ», հարցնում է նա: «Ի՞նչ ես արել իմ ապագայի հետ: Ի՞նչ ես արել քո կյանքում»։

Եվ ես նրան ասում եմ, որ փորձել եմ։ Որ փորձել եմ հիշողությունը վառ պահել, որ փորձել եմ պայքարել նրանց հետ, ովքեր մոռանալու են։ Որովհետև եթե մոռանանք, մեղավոր ենք, հանցակից ենք։

Եվ հետո ես բացատրեցի նրան, թե որքան միամիտ ենք մենք, որ աշխարհը գիտեր ու լռում էր։ Եվ այդ պատճառով ես երդվեցի երբեք չլռել, երբ և որտեղ մարդիկ տառապեն տառապանքներին և նվաստացումներին։ Մենք միշտ պետք է կողմ լինենք։ Չեզոքությունը օգնում է ճնշողին, ոչ երբեք զոհին: Լռությունը քաջալերում է տանջողին, ոչ երբեք տանջվողին: Երբեմն մենք պետք է միջամտենք: Երբ վտանգված են մարդկային կյանքեր, երբ վտանգված է մարդկային արժանապատվությունը, ազգային սահմաններն ու զգայունությունը դառնում են անտեղի: Այնտեղ, որտեղ տղամարդիկ կամ կանայք հալածվում են իրենց ռասայական, կրոնական կամ քաղաքական հայացքների պատճառով, այդ վայրը պետք է, այդ պահին, դառնա տիեզերքի կենտրոնը:

Իհարկե, քանի որ ես հրեա եմ, որը խորապես արմատավորված է իմ ժողովուրդների հիշողության և ավանդույթների վրա, իմ առաջին արձագանքը հրեական վախերին, հրեական կարիքներին, հրեական ճգնաժամերին է: Որովհետև ես պատկանում եմ տրավմատացված սերնդին, որը զգացել է մեր ժողովրդի լքվածությունն ու մենությունը: Ինձ համար անբնական կլիներ հրեական առաջնահերթությունները իմը չդնել. Իսրայելը, խորհրդային հրեաները, հրեաները արաբական երկրներում… Բայց կան ուրիշներ, որոնք նույնքան կարևոր են ինձ համար: Ապարտեյդը, իմ կարծիքով, նույնքան զզվելի է, որքան հակասեմիտիզմը: Ինձ համար Անդրեյ Սախարովի մեկուսացումը նույնքան խայտառակություն է, որքան Յոզեֆ Բիգունի բանտարկությունը։ Ինչպես Solidarity-ի և նրա առաջնորդ Լեխ Վալեսայի այլակարծության իրավունքի ժխտումը: Եվ Նելսոն Մանդելայի անվերջ բանտարկությունը.

Այնքան անարդարություն և տառապանք կա, որ աղաղակում է մեր ուշադրությունը՝ սովի, ռասիզմի և քաղաքական հալածանքների զոհեր, գրողներ և բանաստեղծներ, բանտարկյալներ շատ երկրներում, որոնք կառավարվում են ձախերի և աջերի կողմից: Մարդու իրավունքները ոտնահարվում են բոլոր մայրցամաքներում. Ավելի շատ մարդիկ ճնշված են, քան ազատ: Եվ հետո նաև կան պաղեստինցիներ, որոնց դժբախտության նկատմամբ ես զգայուն եմ, բայց ում մեթոդները ես ափսոսում եմ: Բռնությունն ու ահաբեկչությունը լուծում չեն. Ինչ-որ բան պետք է անել նրանց տառապանքների դեմ, և շուտով: Ես վստահում եմ Իսրայելին, քանի որ հավատում եմ հրեա ժողովրդին: Թող Իսրայելին հնարավորություն տրվի, թող ատելությունն ու վտանգը հեռացնեն նրա հորիզոններից, և խաղաղություն կլինի Սուրբ Երկրում և նրա շուրջը:

Այո, ես հավատ ունեմ։ Հավատք առ Աստված և նույնիսկ Նրա ստեղծածը: Առանց դրա ոչ մի գործողություն հնարավոր չէր լինի: Իսկ գործողությունը անտարբերության միակ միջոցն է՝ ամենախորամանկ վտանգը: Սա չէ՞ Ալֆրեդ Նոբելի ժառանգության իմաստը: Պատերազմի հանդեպ նրա վախը վահան չէ՞ր պատերազմի դեմ։

Շատ բան կա անելու, շատ բան կա անելու։ Մեկ մարդ՝ Ռաուլ Վալենբերգը, Ալբերտ Շվեյցերը, մեկ ազնիվ մարդ, կարող է փոխել կյանքի և մահվան տարբերությունը: Քանի դեռ մեկ այլախոհը բանտում է, մեր ազատությունը չի լինի իրական. Քանի դեռ մեկ երեխա սոված է, մեր կյանքը կլցվի տառապանքով և ամոթով: Այս բոլոր զոհերին ամենից առաջ պետք է իմանալ, որ իրենք միայնակ չեն. որ մենք չենք մոռանում նրանց, որ երբ նրանց ձայնը խեղդվի, մենք նրանց կտանք մերը, որ թեև նրանց ազատությունը կախված է մեզանից, մեր ազատության որակը կախված է նրանցից։

Սա այն է, ինչ ես ասում եմ երիտասարդ հրեա տղային, որը մտածում էր, թե ինչ եմ արել ես իր տարիների հետ: Նրա անունով է, որ ես խոսում եմ ձեզ հետ և հայտնում եմ ձեզ իմ խորին երախտագիտությունը: Ոչ ոք այնքան ընդունակ չէ երախտագիտության, որքան նա, ով դուրս է եկել գիշերային թագավորությունից: Մենք գիտենք, որ ամեն պահ շնորհի պահ է, ամեն ժամ՝ ընծա. չկիսել դրանք կնշանակի դավաճանել նրանց: Մեր կյանքերը այլևս միայն մեզ չեն պատկանում. դրանք պատկանում են բոլոր նրանց, ովքեր մեր կարիքն ունեն:

Շնորհակալություն, նախագահ Աարվիկ: Շնորհակալություն Նոբելյան կոմիտեի անդամներ։ Շնորհակալություն ձեզ, Նորվեգիայի ժողովուրդ, այս եզակի առիթով հայտարարելու համար, որ մեր գոյատևումն իմաստ ունի մարդկության համար: